In a case similar to the Gaidry case, New Iberia Extract Co. v. McIlhenny Sons, the New Iberia Company had recently recovered damages against McIlhenny Sons in the Supreme Court of Louisiana, on a similar cause of action, New Iberia Extract Co. v. E. McIlhenny, 182 La. 150 [8 T. M. Rep. 189], the decision having been based largely on the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, cancelling the Mcllhenny Company registration of “Tabasco” as its trade-mark. The trade-mark had been cancelled, first, on the ground that it could not be denominated a technical trade-mark, because it was a geographical name, and, second, on the ground that it was fraudulently obtained, the application falsely stating it had been “in the actual and exclusive use of defendants since 1868.” The Court further held that, as a matter of law, the exclusive right, if any, of the defendant to the use of the name, had expired with its patent in 1887. The Court of Appeals for this Circuit in the Gaidry case took note of these two cases, but held them not reconcilable with the later ruling of the United States Supreme Court in Baglin v. Cusenier, 221 U. S. 680 [1 T. M. Rep. 147], wherein it was held that the fact that the primary meaning of the word “Chartreuse” was geographical did not prevent the acquisition of the exclusive right to its use as the designation of a liqueur made by the monks of the Monastery of La Grande Chartreuse. As a further inroad on the original doctrine that a geographical name could not be used as a trade-mark, the Court cited the case of Hamilton Brown Shoe Company v. Wolf Bros. Sf Company, 240 U. S. 251 [6 T. M. Rep. 169], in which the plaintiff’s right was upheld to the use of “The American Girl” as a trade-mark for shoes. The Court of Appeals quoted from the Chartreuse case as follows:

“If it be assumed that the Monks took their name from the region in France in which they settled in the Eleventh Century, it still remains true that it became peculiarly their designation. And the word ‘Chartreuse’ as applied to the liqueur which for generations they made and sold cannot be regarded in a proper sense as a geographical name. It had exclusive reference to the fact that it was the liqueur made by the Carthusian Monks at their Monastery. So far as it embraced the notion of place, the description was not of a district, but of the Monastery of the Order—the abode of the Monks—and the term in its entirety pointed to production by the Monks.”

And from the Hamilton Brown Shoe Company case the Court quoted:

“We do not regard the words ‘The American Girl,’ adopted and employed by complainant in connection with shoes of its manufacture, as being a geographical or descriptive term. It does not signify that the shoes are manufactured in America, or intended to be sold or used in America, nor does it indicate the quality or characteristics of the shoes. Indeed, it does not, in its primary signification, indicate shoes at all. It is a fanciful designation, arbitrarily selected by complainant’s predecessors to designate shoes of their manufacture. We are convinced that it was subject to appropriation for that purpose, and it abundantly appears to have been appropriated and used by complainant and those under whom it claims.”

In summing up the effects of these two cases, the Court of Appeals said:

“The rulings just referred to establish the proposition that the fact that a word or expression has a geographical meaning does not prevent its appropriation as a trade-mark or as the designation of a manufacturer’s or dealer’s product, when it is so used as not to have a geographical or descriptive signification, nor make legally impossible the assertion in good faith of a claim of exclusive right to use such word or expression for a non-geographical and non-descriptive purpose, even though such use may result or have resulted in its acquiring a new meaning or new meanings separate and distinct from the one it had before.”

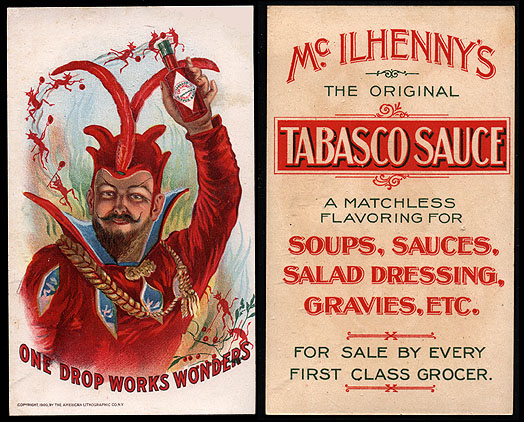

The Court then held that E. McIlhenny did not use the word “Tabasco” as a geographical or descriptive term, and, consequently, that it did not indicate the place of manufacture. Neither did it indicate the kind of pepper which was the principal ingredient, as the pepper at that time was not known as “Tabasco” pepper. All the findings of fact and conclusions of the Court of Appeals in that case are fully applicable to the present case.

The finding of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia that the registration by plaintiff’s predecessor of the trade-mark had been fraudulently obtained, was based on the fact that in the application for registration, it was stated that applicant’s use of the name “Tabasco” had been exclusive, whereas the testimony showed that several other manufacturers, during the preceding ten years, had, to its knowledge, used the word in connection with pepper sauce. From the stipulation in the present case, it appears that the term “exclusive use” had, up to that time, been uniformly held by the Commissioner of Patents to mean “rightfully exclusive” as distinguished from “sole and exclusive,” and that the application was signed on the assurance of reputable counsel, that, in the legal sense of the word, the Mcllhenny use had been exclusive. The name had been used by Edmund McIlhenny and his successors, since 1868, and the five or six other manufacturers who had used it during the preceding few years had been notified of the McIlhenny claim to its exclusive use as a trade-mark. Had the application disclosed such use of the word by others, on proof that it was a wrongful use, plaintiff’s predecessor would still have been entitled to the registration of the trade-mark. Under the circumstances, as thus explained, I think the applicant’s representation of exclusive use of the name was not made in bad faith.

As to the effect of that decree, the Court of Appeals in the Gaidry case held that the cancellation of McIlhenny’s trade-mark could not affect his rights, if he, in fact, had acquired, at that time, a common law technical trade-mark; that a trade-mark, if it exists, exists independently of registration, and that cancellation does not extinguish a right which the registration did not confer, citing Edison v. Thot. A. Edison, etc., Co., 128 Fed. 1018; Capewell Horse Nail Company v. Mooney, 172 Fed. 826.