Fiery Foods & BBQ Central Recommendations

Chile Pepper Bedding Plants... over 500 varieties from Cross Country Nurseries, shipping April to early June. Fresh pods ship September and early October. Go here

Chile Pepper Seeds… from all over the world from the Chile Pepper Institute. Go here

Photos by Harald Zoschke

A pepper garden can only be as good as the original genetic material used to start it–the seed. Bad seed produces unsatisfactory results no matter how skilled the gardener is. At least good seed stands a chance to produce excellent plants and pods. One of the biggest disappointments for the pepper gardener is discovering that the seed planted does not produce the pods it is supposed to produce. Instead of jalapeños, say, the gardener finds an unrecognizable hybrid and realizes that time and energy has been wasted by growing this plant. Therefore, the first step toward a great pepper garden is to select good seed.

Selecting Seed

Home-Grown Seeds. Home gardeners often produce unwanted hybrids (out-crosses) because peppers are notorious cross-pollinators. When different varieties are planted close together in the garden, bees and other insects will carry pollen from flower to flower, cross-pollinating them. The pods of the current year’s plants will be true, but the seed in those pods will produce hybrids thereafter.

Like this bumblebee on a serrano flower, insects will carry pollen from flower to flower, cross-pollinating them

To produce seed that is true to type, individual varieties must be pollinated only by their own pollen. Commercial seed producers avoid cross-pollination by isolating varieties and planting them at least a mile from each other, which is farther than the average bee flies. Home gardeners can produce true seed by isolating peppers from insects and growing them in greenhouses or under netting.

Many pepper gardeners exchange seed with other growers, but this seed may also not grow true to type. Home growers can either ask the sender how the seed was grown, or plant it and see what happens. Gardeners and seed collectors from all over the world send us seed, and the more unusual the variety is, the greater our temptation is to grow it regardless of origin.

Commercial Seed. Seed produced by seed companies is generally more reliable than home grown seed because the companies try to safeguard the genetic purity of the cultivar. They use a systematic seed-growing process, which begins with crop improvement associations in each state. In the association, a plant breeder responsible for developing a specific variety of pepper or other crop produces small quantities of Breeder Seed. It is multiplied into Foundation Seed, which is controlled by the crop improvement association. The association grows the Foundation Seed to produce Registered Seed, which is sold to seed companies to produce Certified Seed for farmers and the general public.

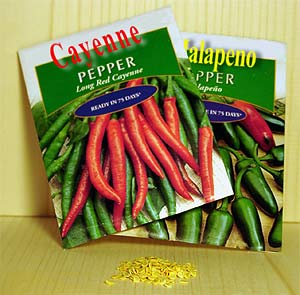

Commercial seed packages

Large seed companies have their own internal process which mirrors the one used by crop improvement associations. Company plant breeders develop Breeder Seed and Foundation Seed for specific varieties. It is then passed on to company seed production managers, who oversee the growing of Registered and Certified Seed. In some cases, the production of Certified Seed is “farmed out” to independent growers on farms distant from each other to avoid cross-pollination.

Unfortunately, some small seed companies and “cottage” seed industries either do not practice proper isolation techniques or buy their seed from growers who do not. Thus, their seed is undependable, and often yields hybrids. Home gardeners should either question small seed companies about their isolation techniques, or confine seed purchases to the major companies. Always buy seed from a reliable seedsman, one who consistently provides varieties true to type, free from disease, and with a high germination percentage. High quality, fresh seed is dependable; cheap seed is neither dependable nor inexpensive.

Growers should check the seed packet for a germination percentage when buying commercial seed. The federal pepper regulations are: seeds with a germination percentage below 55 percent may not be sold; seeds with a percentage between 55 and 85 percent must have the percentage listed on the packet; and seeds with a germination percentage over 85 percent need not have the percentage listed.

Inspecting and Testing Seed. Once the seeds of the selected varieties are in hand, there are several easy culling techniques to increase germination percentage and potential seedling vigor. First, place the seed in a jar of water and discard any that float. These are damaged, partial seeds and those lacking embryos. Next, inspect the seed, preferably under a magnifying glass, and remove any that are undersized, shriveled, discolored, cracked, or otherwise damaged.

Some pepper growers, especially those who use direct seeding methods, like to know the expected germination percentage for each variety, so they conduct a germination test in the late winter. To conduct this test, place the seed between damp (not sopping wet) layers of paper towels, with no two seeds touching. Transfer the layers of towels to a plastic bag (preferably self-closing) and then set it on something warm, such as heating cables, or on top of the hot water heater or refrigerator. After two weeks have passed, enough time for the average pepper seed to sprout, open the bag and count the sprouted seeds. Divide the number of sprouted seeds by the total number of seeds used to arrive at the approximate germination percentage. There are seed testing laboratories in every state that will conduct this test for a fee, but allow the agency at least two months to run the test.

Another germination test method: damp paper tissue on a plate, covered with plastic wrap with some ventilation holes poked into it

Factors Affecting Seed Germination

Pepper seed germination even under optimum conditions is often slow and irregular. Although some studies have shown that pepper seeds germinate very quickly and have very high germination percentages under high temperatures, some exotic varieties we’ve grown have taken upwards of five weeks to germinate at ideal temperatures.

Basically, pepper seeds need warmth, oxygen, and moisture to germinate. However, home gardeners should consider other factors that influence germination before planting seed.

Pod Maturity, Seed Dormancy, and After-ripening. The maturity of the pods at the time seed is extracted greatly influences germination. Immature pods will usually produce infertile seed, which will not germinate. In a 1986 study conducted at the Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station, R.L. Edwards and F.J. Sundstrom extracted seed from red and orange pods of tabasco peppers harvested 150, 195, and 240 days after transplanting. They tested the seed for germination percentage and found, as expected, that seed from the red pods outperformed seed from the orange pods in all cases. However, they also discovered that the germination performance of seed from the red pods decreased as the season progressed; the 81 percent germination at 150 days dropped to 63 percent at 240 days. This study indicates that seeds from the earliest picked red pods will have the highest germination percentage, at least for Tabasco peppers.

Some peppers, like other perennials, produce seed which does not immediately germinate when extracted from the fresh pods and planted, even though all environmental factors favor germination. This survival mechanism, called dormancy, helps prevent germination in the fall, just before cold weather would kill the seedlings. However, because peppers are perennials that are grown as annuals in the U.S., the degree of dormancy varies from variety to variety. The strongest dormancy appears in wild varieties, such as chiltepins, which overwinter well. Hybrids, grown as annuals, have the weakest degree of dormancy.

In the same 1986 study, Edwards and Sundstrom also tested the process called after-ripening, which is the gradual drying of the seed so that its moisture content drops from about 34 percent to 7 percent over a three-week period. In one test, the germination percentage of seed from red pods increased from 58 percent to 94 percent after 21 days of after-ripening. No significant effect of after-ripening on seed from immature pods occurred.

This study, combined with our observations over the years, indicates that the highest germination percentage of pepper seed occurs in seed harvested from early red pods that are dried for one to four months. Some varieties have other colors at maturity, such as orange or yellow, so growers should pick these pods for seeds when that color reaches its deepest hue.

Temperature and Irrigation. During the winter of 1934-35, H.L. Cochran of the Georgia Experiment Station conducted a classic study of the effects of temperature and irrigation on the germination of bell pepper seed. Two flats of seeds were placed in each of five greenhouses which were kept at the following temperature ranges (degrees F.): 40 to 50, 50 to 60, 60 to 70, 70 to 80, and 90 to 100. In each greenhouse, one of the flats was surface irrigated by a simple watering can, and the other was sub-irrigated by placing it in an inch of water in a large tank until the soil had taken up enough water to dampen the surface.

Both the percentage and speed of germination increased dramatically as the temperature increased. No seeds germinated at 40 to 50 degrees, and the percentage increased from 59 percent at 50 to 60 degrees to 74 percent at 90 to 100 degrees. The rate of seedling emergence also dropped from 30 days to 6 days at those same temperature ranges. Also interesting was the fact that seeds which did not germinate after 45 days at 40 to 50 degrees sprouted in 6 days when transferred to the 90 to 100 degree greenhouse.

The highest germination percentage occurred at 70 to 80 degrees (79.5 percent), and the quickest germination occurred at 90 to 100 degrees (6 days, 73 percent). Watering by sub-irrigation reduced the germination percentage at all temperatures, probably because that procedure reduced the soil temperature more than surface irrigation.

The inescapable conclusion from Cochran’s experiment, and many subsequent ones, is that for optimum germination, pepper seed should be grown at 70 degrees or more and should be watered with warm water from the top.

Pre-Planting Treatments. Cochran also experimented with soaking some of the seeds in water before planting, but he only soaked them for six hours. Soaking the seeds for two or three days can sometimes aid the germination rate and percentage, but probably not a significant amount.

Germination problems often occur in pepper seeds with a particularly tough seed coat, such as wild varieties like the chiltepin. Growers should soak the seeds for 5 minutes in a 10 percent bleach solution, rinse well, and then plant. This procedure will soften the seed coat so the seed will germinate more quickly. If the seed has not germinated in 14 days, the bleach treatment can be repeated.

Another treatment that increases the germination rate and percentage in peppers is gibberellin, a plant hormone. Seed should be soaked for 1 to 2 hours in a 100 parts per million (ppm) solution. Gibberellin is available from some online nurseries.

Peppers are susceptible to plant pathogens on the seed coat such as bacterial leaf spot and tobacco mosaic virus. Fortunately, a relatively simply procedure has been developed to remove these pathogens. First, soak the seeds for one-half hour in a 10 percent (weight to volume) trisodium phosphate (TSP) solution. (TSP is available at most hardware stores as a wall cleaner.) After soaking, rinse the seeds in thoroughly in cold running water. Second, soak the seed in a 10 percent bleach solution for 5 minutes, then rise thoroughly in cold, running water until all the bleach odor is gone. Dry the seed and sow within a month of treatment.

Seedlings, 3 days after germination

One of the most ingenious pre-planting treatments we’ve come across is the technique developed by Charlie Ward of Virginia Beach, Virginia. Charlie was bothered by the low germination rates of chiltepin seeds and then read an article about the spread of chiltepins by birds. He decided to prepare a treatment that simulated the alimentary canal of birds and gathered seagull excrement, which is plentiful in Virginia Beach. Then he made a slurry out of the excrement and water, added the seeds, and let the mixture sit in the sun for a few days. After extracting the seeds with forceps and planting them, Charlie discovered that his germination rate increased to 95 percent!

Such a technique can be utilized by pepper gardeners who also raise birds such as parrots, finches, and canaries. These birds will readily eat small red pods because they contain vitamin A, which improves the coloration of the birds’ plumage. The droppings can be collected on newspaper and the seeds can be removed and planted.