Collected by Dave DeWitt

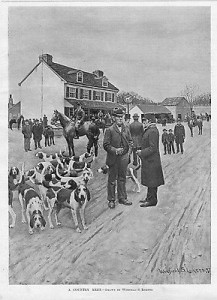

In England the Yule-log, the boar’s head and the wassail bowl were in olden time the features of the festival. The first-named was a huge log of oak, decked with holly wreaths and mistletoe. At Christmas it was dragged into the great hall by all the members of the household, the merriest of them, dubbed the Lord of Misrule, seated upon it singing songs and making jests. It was rolled into the fireplace and made a mighty blaze all day and night. This was a survival of the Scandinavian custom of kindling great fires at Yuletide, the winter solstice. The boar’s head was the dish of honor on the Christmas table, and was brought in on a huge platter garnished with leaves and fruit. It was a German custom, and down to the present day the German emperor has sent each Christmas a boar’s head as a present to the Queen of England. In the Southern states [of the U.S.], planters and farmers with one accord keep open house at Christmas. If there are girls in the family, they invite other girl friends to spend Christmas week with them, and their brothers extend a like invitation to their masculine friends—in an arrangement that makes the big country-houses brim over with fun and jollity from Christmas Eve to New Year’s and after. Eggnog frolics, candy-pullings, charades, dances and every description of games that can be played indoors or out and indulged in, and horseback-riding, driving, fox-hunting, bird-hunting, and every description of equestrian exercise are participated in by both sexes. The girls, however, do not take part in the fox-hunting at night, when oft-times the part is out until early dawn, riding through branch and brier, swamp and thicket, over fallen logs and accumulated brush-heaps, into holes and over ditches and fences with reckless fearlessness.

In the Southern states [of the U.S.], planters and farmers with one accord keep open house at Christmas. If there are girls in the family, they invite other girl friends to spend Christmas week with them, and their brothers extend a like invitation to their masculine friends—in an arrangement that makes the big country-houses brim over with fun and jollity from Christmas Eve to New Year’s and after. Eggnog frolics, candy-pullings, charades, dances and every description of games that can be played indoors or out and indulged in, and horseback-riding, driving, fox-hunting, bird-hunting, and every description of equestrian exercise are participated in by both sexes. The girls, however, do not take part in the fox-hunting at night, when oft-times the part is out until early dawn, riding through branch and brier, swamp and thicket, over fallen logs and accumulated brush-heaps, into holes and over ditches and fences with reckless fearlessness.

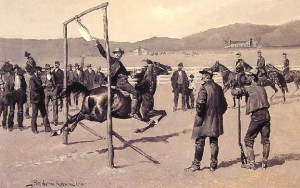

A great diversion at Christmas among [Negroes] and some of the white people of the South is gander-pulling. It is a sport so cruel that its popularity is anything but a credit to those that patronize it, /a number of plump ganders, whose necks are well-greased, are suspended at the regulation height, in much the same manner as rings arranged at ordinary tournaments The “knights” who enlist from the prizes dash out on their horses in courtly fashion and grab each of those down-hanging necks in succession as they pass, the most skillful rider and “puller” winning the prizes. The affair is usually an all-day outing—dinners and all manner of refreshments are sold on the grounds, musicians are present to enliven the scene, and the demise of these devoted members of the goose family is attended with much demonstration and ceremony.

A great diversion at Christmas among [Negroes] and some of the white people of the South is gander-pulling. It is a sport so cruel that its popularity is anything but a credit to those that patronize it, /a number of plump ganders, whose necks are well-greased, are suspended at the regulation height, in much the same manner as rings arranged at ordinary tournaments The “knights” who enlist from the prizes dash out on their horses in courtly fashion and grab each of those down-hanging necks in succession as they pass, the most skillful rider and “puller” winning the prizes. The affair is usually an all-day outing—dinners and all manner of refreshments are sold on the grounds, musicians are present to enliven the scene, and the demise of these devoted members of the goose family is attended with much demonstration and ceremony.

There were no Christmas celebrations in my old Puritan home in Swansea, such as we have in all New England homes to-day. No church bells rung out in the  darkening December air; there were no children’s carols learned in Sunday-schools; no presents, and not even a sprig of box, ivy, or pine in any window. Yet there was one curious custom in the old town that made Christmas Eve in many homes the merriest in the year. It was the burning of the Christmas candle; and of this old, forgotten custom of provincial towns I have an odd story to tell.

darkening December air; there were no children’s carols learned in Sunday-schools; no presents, and not even a sprig of box, ivy, or pine in any window. Yet there was one curious custom in the old town that made Christmas Eve in many homes the merriest in the year. It was the burning of the Christmas candle; and of this old, forgotten custom of provincial towns I have an odd story to tell.

The Christmas candle? You may never have heard of it. You may fancy that it was some beautiful image in wax, or like an altar-light. This was not the case. It was a candle containing a quill filled with gunpowder, and its burning excited an intense interest while we waited for the expected explosion.

Sources:

Edward Haldane, “Around the World with Santa Claus,” Home and Country, Volume 11, 1895.

Hezekiah Butterworth, The Parsons̓ Miracle: And My Grandmothers̓ Grandmothers̓ Christmas Candle; Christmas in America. Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1894.

![Bring in the Boar's Head [Illustrated London News]](https://www.fieryfoodscentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Bringing_in_the_Boars_Head-220x300.jpg)