Curry-Making [Made Complicated]

Editor’s Note: I added the extension in the title because that’s exactly what this long-winded, poorly- organized, and overly-complicated demonstration is. But it’s also funny, in a British sort of way. Curry was all the rage in England post-Raj, and many Brits thought that they could spread it to the States. But the culture in the former colonies had no ties to India, so it took a long time for Indian cuisine to become an ethnic favorite. And curries haven’t really caught on in the States. The credit for this piece of food history trivia is: As Demonstrated by Colonel Kenny-Herbert and published in the Cookery Annual of 1895 by The American Kitchen Magazine, Volume 5. The Home Science Publishing Co., Boston, Massachusetts, 1896.

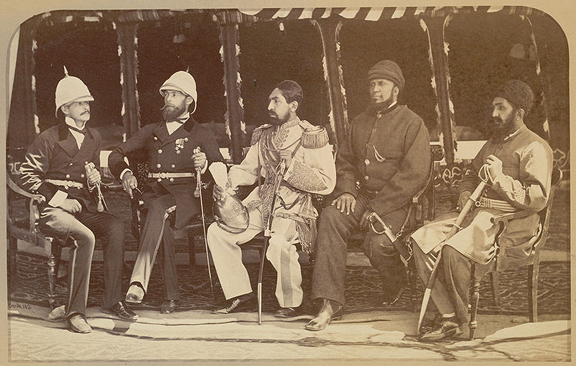

| Photo Above: Portrait of British officers and Amir Yakub Khan. John Burke, 1879 |

I HAVE been asked, ladies and gentlemen, to exemplify to you practically this evening my system of making curries. Now I need scarcely tell you that, having served for over thirty years in India, and at the acknowledged headquarters of this branch of cookery—Madras—I have had some little experience on this subject. Then, as I have for many years taken deep interest in the cook’s art generally, I have paid greater attention, perhaps, to the practical side of the work than most of my compatriots in the land of India, who, while excellent judges, no doubt, of what a curry should be on the table, never put their hands to one in the stewpan in their lives. Even in India there are curries and curries, more of them bad, indeed, than good. Everything depends upon the education of the cook.

The native preparations in the majority of cases could scarcely be eaten by civilized Europeans. They are apt to be too greasy, too hot, and too strongly impregnated with garlic. Good curries, from our standpoint, are the result of a blend between European and Asiatic cookery, and whenever you get a specially nice one depend upon it the credit is more due to the mistress of the house than to the cook. I propose to show you in the first place the ordinary moist Madras curry, then a Malay or Ceylon curry, and if I have time, a dry Madras curry. We will not discuss the question of powders and pastes, for most people can choose for themselves, many good sorts being nowadays procurable without trouble in London.

Now I hope that you will not think my system of curry-making is too troublesome. It may seem a little elaborate to some of you, but if you note the gradual sequence of the different stages in the process you will find that it is not a very intricate task after all, while if you practice it once or twice you will, I am sure, find it easy. Nothing, after all, can be done without trouble, and I feel sure that no practical worker present would shirk a little extra pains in order to secure success—the dearest prize to all cooks who have their business at heart.

The proportions I am about to give you will be found reliable approximately for one pound of meat, or fish, a full-sized chicken, or a pound of vegetables. The vessels I shall use are French earthenware casseroles which I consider by far the best for curry-making. They are admirable for slow cooking, and are very easily cleaned. Curries may be left in them without any risk, and may be served in them without dishing up if a napkin or frilled paper be pinned neatly around them. As curries improve by a day’s keeping this is worth noting.

|

| Madras group of Tamil Natives at the Pier |

I prepare the meat as follows: Uncooked veal, mutton, lamb, pork, or beef, in three-quarter inch squares; chicken as for fricassee, but making three pieces of the breast, cross cut, two of each thigh, and two of each leg, for chickens in India are used when much smaller than English birds. Fish I cut into squares like meat; cucumbers, vegetable marrows, potatoes, and Jerusalem artichokes in neat pieces, cauliflower in sprigs, hard boiled eggs in halves, etc. I then weigh four ounces of onion, Portugal preferred, which I chop up quite small; I put two ounces of fresh butter into my casserole, set it over a moderate gas fire, and when the butter has melted, I put in the minced onion and cover the pan, leaving the onion to fry gently, softening it thoroughly, and gradually browning. There must be no burning, but it must brown.

While this is going on I prepare the “curry stuff,” or mixture, as follows: —I put into a soup-plate a tablespoonful and a half of curry powder, a dessertspoonful of curry paste, a saltspoonful of salt, and a tablespoonful of rice flour. These I turn to a paste by moistening them slightly with stock or milk, amalgamating the whole well. Next let us make the nutty infusion. In a small bowl I put one tablespoonful and a half of desiccated cocoanut and one of ground sweet almonds, and pour over them a breakfast-cupful of boiling water. This I cover up to infuse, and leave until the end of the whole process.

By this time the onions have cooked sufficiently, so I add to them the curry mixture, which I carefully fry for ten minutes at least, so as to work away the crudity of the curry powder. This step is absolutely essential, and its omission in English recipes and in ordinary practice is the cause of the’ roughness in curries so much complained of by foreign artists. When well fried, I moisten, as in sauce-making, by degrees, with the best broth or stock at hand—fish broth for fish, milk or vegetable broth for vegetables, giblet broth for chicken, and so on. A pint will be found enough for the quantity of meat under treatment.

When all has been stirred in I accelerate the heat somewhat, and then prepare the very necessary flavoring of green ginger, and the subacid. The former is contributed in a rasped or pounded state to the extent of a generously filled teaspoonful; the latter by a teaspoonful of red currant jelly with the juice of half a lemon. If available, a dessertspoonful of good chutney may also go in. I now bring the contents of the pan to the boil, and add, after browning it in a saute pan in an ounce of butter, the uncooked meat, reducing the heat at once to simmering. The process now cannot be too gently conducted—an hour and a half is not too much to allow. So while this is going on I will show you a Malay or Cevlon curry.

For this I will take a pound of “halibut cut into squares, and half a pound of cucumber which has been cut into small fillets, and separately cooked, simply as garnish. I prepare the onions as in the first curry, using the same quantity of them and of butter, but not browning them. I only fry them till they are soft. I make the same nutty infusion. I mix the following “curry stuff”:—In a soup-plate I put one large tablespoonful of creme de riz, or rice flour, one dessertspoonful of powdered turmeric, spoonful of salt, a spoonful of powdered cinnamon, and one of powdered cardamoms. I mix these to a paste as in the first case, using fish broth or milk. I add this “curry stuff” to the fried onions as soon as the latter are soft, and cook it for at least seven minutes to get rid of the crudity of the turmeric.

Now I begin to moisten with a pint of fish broth, as in the case of the first curry, adding a tablespoonful of grated green ginger, and the cocoanut and almond, after straining off the milky liquid produced by the infusion which I put aside for the present. I have next to bring the contents of the casserole to the boil, and then simmer twenty minutes to extract the flavor of the ginger, etc.; then I must pass the whole through a hair sieve. The next thing I do is to re-heat the strained sauce, for at present it is actually nothing more than sauce, and then put in the fish, which is just simmered till tender, very carefully or it will cook to pieces. Lastly I put in the pieces of cooked cucumber, the squeeze of a lemon, and the strained nutty infusion, with a tablespoonful of cream. The curry is now ready to be served with rice, dished separately.

Please note the following points in this curry:—First that it is made without curry-powder, next that it requires a larger quantity of green ginger than the ordinary Madras curry, then that its sauce is strained through a hair sieve, for it should be smooth and creamy. Observe too, that I cook the strained cocoanut and almond in the sauce, besides saving the infusion for final addition. The best Ceylon curries are made locally with shell-fish —prawns, crabs, and langoustes (the sea cray fish). In England we can also use shrimps and lobster. Salmon or any other firm fish is excellent in this manner. It is customary to associate cucumber or vegetable marrow fillets with these curries, and very nice ones are made with vegetables alone—sprigs of cauliflower, both kinds of artichokes, mushrooms (which are overwhelmed in ordinary curry by the condiments), and well soaked haricots are specially adapted to this method. Hard boiled eggs cut in halves lengthwise are often put into a Ceylon curry sauce, while poached eggs masked with it are generally much liked. Cold cooked fish may be thus resuscitated successfully, while a fricassee of cold cooked chicken a la Cingalese is indeed excellent.

Now let us return to our Madras curry. Time does not admit of its being sufficiently simmered, I must therefore assume that this has been done, and that the time has come for the last touches. I taste the sauce to see whether the subacid is sufficiently noticeable, also whether any more salt is needed. Corrections are made accordingly, and then the nutty infusion is poured into the curry through a strainer, the nutty sediment being well pressed to expel all the milk. The curry can now be served, rice dished separately accompanying.

Kindly observe a few salient points in this curry also. Why do I use rice, flour? I do so because I want to absorb the butter as by liaison. Few Indian cooks take this trouble unless instructed to do so. The consequence is that there is generally a most undesirable exudation of the fatty element in their curries, which, the moment extreme heat passes off, becomes greasy. A halo of this surrounding a curry is not an attraction to be encouraged. You may have noticed that I employ both powder and paste. This, I think, is quite necessary to produce a Madras curry at its best, because there are ingredients in the paste which cannot enter into a powder—tamarind, green ginger, a very little garlic, almonds, mustard oil, etc.

The green ginger and the nutty infusion are important features rarely attended to in England, and yet they are easily got. You have seen me use the desiccated cocoanut and ground sweet almonds sold for pudding making. You will find that the “milk” thus produced makes a very good substitute for the fresh cocoanut extract used in India. Green ginger can be got any day you like of the herbalists in Covent Garden.

|

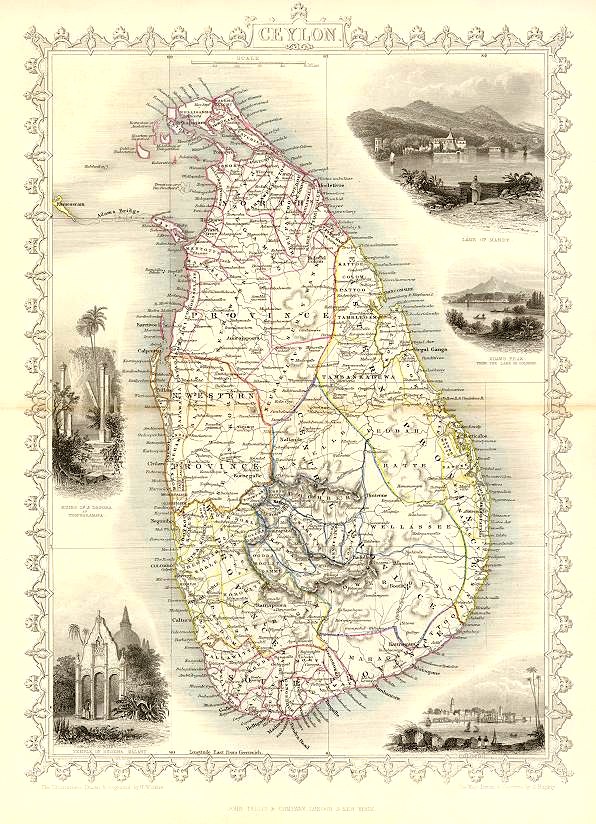

| Tamarind, a traditional ingredient in Madras curries |

Next as regards the subacid. Apple is, I know, recommended by many. I see no harm in it, but it is not nearly as good as tamarind, the ingredient used in India. I am personally quite contented with red currant jelly blended with lemon-juice. This dissolves easily, can be added as desired, and provides all that is wanted. I have seen strawberry jam advocated by a very clever writer on the aesthetics of cookery, but in this the lady is mistaken. Jelly is far better than jam, as all practical cooks know, when the object is to obtain sweetness without lumpiness in a sauce. In good strawberry jam the fruit should be almost whole. There is another thing. In some recipes you find that you are advised to rub the pieces of chicken or meat with curry powder, and fry them with onions. This is quite unneccesary in my system. All that is necessary is to toss the meat in butter in a saute-pan sufficiently to “seize it,” and then to pass it into the curry sauce. We have enough onions and curry stuff already in the composition.

Touching curries made of cooked meats, it is a mistake to say that these are not worth eating. They can be turned out very well indeed by my method, provided you take care to have a really good moistening broth, assisted, say, with an ounce of meat glaze, and if you will remember these points: Cooked meat does not need re-cooking, therefore, when you have got your well-flavored sauce ready, slip in the meat, and let it marinate as long as you can therein without any cooking whatever. Then, when you want to serve, bring the contents of your casserole very gently to steaming point, and send it up without delay.

I have no time, I much regret to say, to make you a dry curry, for though it is an easy thing to manage, it demands a somewhat tedious process if you desire to get the proper dryness with the proper tenderness. It is simply got by very gentle reduction. But I will conclude by doing you some rice in the ordinary Madras way.

Choose the best Patna rice, and do not wash it. If you use a roomy vessel with plenty of fast boiling water any impurity there may be rises with the scum, and can be taken off. But you will find very little of this. No sane person washes macaroni. Rice should be treated in the same manner, when you know that it has been refined, as the best varieties always are.

(a) For from four to six ounces of uncooked rice choose a four-quart, or even larger, stew-pan; three-parts fill this with water and set it on to boil, putting into it a dessertspoonful of salt, and the juice of half a lemon.

(b) While the water is coming to the boiling point sift on a sieve and weigh the amount of rice you require.

(c) Put a small jug of cold water within easy reach of the range.

(d) As soon as the water boils freely, cast in the rice, and with a wooden spoon give it occasionally a gentle stir round.

(e) Mark the time when the rice was put in, and in about ten or twelve minutes begin to test the grains by taking a few of them out with the spoon, and pinching them between the finger and thumb.

(f) When the grains feel thoroughly

softened through, yet firm, stop the boiling instanter by dashing in the jugful of cold water.

(g) Drain off the water completely on a large .wire sieve, returning the rice to the hot stew-pan; shake this well, set it on the corner of the hot plate, and cover it with a clean hot napkin, so that the rice may dry, repeating the shaking every now and then to separate the grains.

(h) To detach the grains which always adhere to the bottom put in a quarter of an ounce of butter. As this melts the grains will come away. Use a large two pronged steel fork to work the rice loosely.

The drying process will take from eight to ten minutes at the least, and must not be hurried. Even wellboiled rice will’ not come to the table satisfactorily unless it has been drained and dried as I have described.

Raw rice of good quality swells to four times its original bulk when boiled; it therefore requires plenty of water when undergoing that process.

Search our recipe database for easy or advanced curry recipes.