By Paul Ross

|

Recipes:Suban-Ick

|

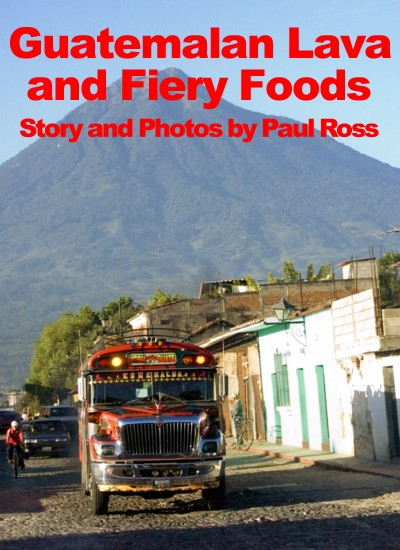

Dotted with more than 30 volcanoes, Guatemala is the kind of country where folks like to take the family on a Sunday afternoon picnic up the slopes of an erupting peak, straight past signs cautioning “unstable ground and dangerous fumes.” Then the survivors stand atop a crumbling crater edge, breathing clouds of Mother Earth-knows-what, while staring precipitously down onto exploding lava. Me, I prefer heat that’s more predictable, the kind that’s served on a (non-tectonic) plate. Fortunately, you can find both kinds in Guatemala.

Guatemalan cooking today is the result of centuries of blending Spanish dishes and techniques with indigenous ingredients and traditions. This small Central American country squeezes mountains, jungles, rainforests and beaches on a narrow strip of land between the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.

An indoor produce market.

In Antigua, a charming colonial city about an hour from the capital, Guatemala City, Maria Mercedes Beteta updates traditional dishes at her three restaurants. The most famous of the three, La Fonda de la Calle Real, rambles through the an old Spanish Colonial home in the heart of the city. It even has a restored colonial kitchen (in addition to the restaurant’s kitchen) where Maria demonstrates cooking on a popular morning TV show. Chairs with plaques bearing the names of honored guests (from film director Francis Ford Coppola to the King of Spain) attest to the celebrity drawing-power of the restaurant; while I was in Antigua, staying at Maria’s hotel across the street, I saw a film crew dining regularly at the restaurant.

Maria Mercedes Beteta in her kitchen.

Beteta is an earnest promoter of her country’s unique dishes. Explaining the origins of Suban-Ick, one of her specialties, she says: “In the Cakqchiquel dialect, it means ‘corn dough’ and ‘hot.'” Beteta collected the recipe from the village of San Martin Jilotepeque, in the tate of Chimaltenango. The dish has a thick, spicy, brown sauce which, in addition to a trio of meats, is loaded with vegetables, including guiskil, which tastes like a hybrid of squash and cucumber. (I would substitute chayote squash if you can find it.) Beteta has adapted the recipe, which is traditionally prepared in an underground pit, for the modern kitchen. And I am happy to report that she has not “adjusted” the heat level to accommodate foreign visitors; her Suban-Ick has plenty of kick, principally due to the inclusion of the chiltepe pod (chiltepin), a potent little number revered locally as “the healing pepper” because of its reputed ability to cure stomach problems. Beteta also crafts a killeradobado sauce, which is great for steak, but I find it even better on pork.

Irma de Guerra in her kitchen.

More basic, homestyle cooking can be found at the house of Irma de Guerra, a grandmother who has opened her home to board students from the more than 50 Spanish language schools based in Antigua. Senora de Guerra serves up hearty meals to complement the total “immersion-learning” environment. Here, locals eat black beans at least twice a day, and de Guerra’s breakfast, frijoles negros, make a solid start to any school day. But the most valuable lesson I learned from the señora was how to turn the simple black bean into a satisfying soup.

Irma serves her students.

Together with corn and squash, beans are part the trilogy of indigenous American foods which have remain as primary as they were in pre-colonial times. Vincent Stanzione, a North American scholar who has lived among the Tz’utujil Maya of Lake Atitlan since the ’80s, described the trilogy in his book, Favorite Recipes from Guatemalla. “The Mayan people of Meso-America have resisted change more tenaciously in their diet than in any other area of culture,” he writes. “Today as in the past they remain Ixim Winaq, “Corn People.” But in addition to corn, beans and squash, the Mayan people of Guatemala also honor a fourth food deity: chile. According to Stanzione, traditional Guatemalan meals always include rikb’al, or “chileness.” Chileness achieves perfection in the classic Guatemalan dish pepian. Hot, hearty, simple yet complex, pepian is not unlike Mexican pipian, a version of mole made with tomatoes, onions, dried chiles and pumpkin seeds, all toasted then blended together into a smooth sauce. In Antigua, pepian has as many variations as there as cooks; it is never bad and is quite frequently great.

The food and the weather get hotter as you head east, peaking in the town of Livingston, center of Guatemala’s Garifuna culture. The feeling there is decidedly Caribbean and the Garifuna people are descended from Arawak and Carib Indians mixed with Africans who were once imported as slaves. In this tropical idyll there’s sport fishing, sandy beaches, irresistible punta music and tapado, a fish stew almost worth the trip in itself.

From the tops of Guatemala’s volcanoes to the shores of her Caribbean beaches, this country offers unmatched cultural and culinary delights. Guatemala is also one of the few remaining vacation destinations where the U.S. dollar has value and the cultures and scenery are so intact. So try the recipes, sample the food and then try the country itself. It’s hot.

Comida Tipica:

A sampling platter of traditional Guatemalan

food (pepian. subanick, caquik, pache, rice and

tortilla) from La Fonda de la Calle Real in Antigua.

Suban-Ick

This dish is wrapped in banana leaves, which give it a subtle, earthy flavor. Serve the dish with plain corn tamales, fresh corn tortillas or rice. It takes a bit of effort, but it produces enough for a party, so make this dish for a special occasion.

The Sauce:

3/4 cup water

30 plum tomatoes, halved

1 medium onion

1 large potato, peeled and quartered

1 large chayote squash, peeled and quartered

4 medium tomatillos, husked and chopped

6 red bell peppers, stemmed and seeded

2 cayenne chiles, seeds and stems removed

1 pasilla chile, seeds and stem removed

1 chile piquin, seeds and stem removed

1 guajillo chile, seeds and stem removed

3 chiltepin chiles (add more for extra heat)

3 bay leaves

2 sprigs fresh thyme

1/3 teaspoon powdered annatto seeds (achiote)

Salt and pepper to taste

The Meat:

1/4 cup vegetable oil

2 1/2 pounds chicken pieces

1 pound country-style pork ribs

1 pound stew beef, cubed

1 package frozen banana leaves, thawed

To make the sauce, in a large pot over medium high heat, combine all of the ingredients except the annatto. Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer until the potatoes are cooked, about 30 minutes. Remove the pot from the heat and allow it to cool. In a separate bowl, add just enough water to make a thick paste of the annatto powder then add that to the rest of the mix. Working in batches, blend in a food-processor and reserve.

To make the meat, pour the oil into a large, heavy-bottomed skillet over medium high heat and working in batches, sear the chicken, pork and beef. Remove them from the heat.

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F.

Wash and dry the banana leaves, then cut them in half lengthwise. In a very large clay pot or Dutch oven, arrange the leaves in the bottom of the pot, emanating in a fan pattern. Arrange the browned meats on the bed of leaves, then pour the blended sauce over the meat. Fold the banana leaves, one at a time, over the top of the meat. Anchor the leaves with a small plate, then cover the pot and bake for 1 hour.

Yield: 8 to 12 servings

Heat Scale: Medium to Hot

Pork in Adobado Sauce

Note that this delicious recipe requires advance preparation.

2 pounds tomatoes, halved and seeded

10 cloves garlic

1 medium onion

2 teaspoons red chile powder

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

1 teaspoon ground cumin, or more, to taste

1/4 teaspoon ground allspice

1/4 teaspoon oregano

White vinegar, to taste

6 pork chops or beef steaks

Preheat the broiler.

Arrange the tomatoes, garlic cloves and onion on baking sheet and broil 5 to 10 minutes, turning frequently, until the vegetables are softened and slightly charred around the edges. In a large bowl, combine the roasted vegetables with the rest of the ingredients, except the white vinegar.

Working in batches, process the mixture in a food processor. Do not puree, but pulse until the mixture resembles a thick, chunky sauce. Add the white vinegar to tasted.

Put the pork chops or beef steaks in a large, shallow dish and pour the sauce over them. Cover the dish with plastic wrap and refrigerate overnight or up to three days, as they do in Guatemala.

One hour prior to serving, preheat a grill to high heat. Remove the meat from the sauce, wiping away any chunks and grill to your desired level of doneness.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Mild

Pepian de Pollo

Traditionally, this dish is made with poached chicken, but you can save time by using store-bought rotisserie chickens. Just make sure you buy chickens without any special flavoring; if that’s all you can find, try to remove all of the skin. You can use any kind of dried red chile for this recipe; anchos, guajillos, pasillas, whatever you have on hand. Look for ingredients like canela and masa harina in the Mexican foods section of your supermarket, at a Latin American grocery, or online. Serve the pepian with plenty of white rice and fresh corn tortillas.

6 plum tomatoes

8 tomatillos, husked and washed

1 medium onion, unpeeled

4 cloves garlic, unpeeled

1/2 cup sesame seeds

1/2 cup shelled pumpkin seeds

3 dried red chiles, stemmed and seeded

1 (2-inch piece) canela or Mexican cinnamon

8 whole cloves

3 whole allspice berries

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

6 cups chicken stock

2 ounces semisweet chocolate, chopped

1/4 cup masa harina mixed with 1/2 cup water

2 large rotisserie chickens, cut into pieces

3 sprigs fresh cilantro

In a large cast iron skillet, toast the tomatoes, tomatillos, onion and garlic until they are slightly blackened. Remove them from the pan and allow them to cool before peeling, coarsely chopping and adding to the blender.

In the skillet, toast the sesame seeds, pumpkin seeds and chiles until the sesame seeds are golden. Add the seeds and chiles to the blender.

Add the canela, cloves and allspice berries to the skillet and toast until aromatic. Add the spices to the blender and puree all of the ingredients together completely. Press the mixture through a sieve.

In a large enameled Dutch oven, heat the vegetable oil over medium high heat. Add the pureed mixture and fry for about 5 minutes. Add the chicken broth and stir to combine. Add the chocolate and the masa harina mixture and stir again. Bring the mixture to a boil, add the chicken pieces, then reduce the heat and simmer about 20 minutes. Garnish with the cilantro.

Yield: 8 to 12 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Tapado (Garifuna Seafood Stew)

Tapado often contains a wide variety of seafood: squid, crab, shrimp, red snapper, sea bass, or even shark. If you have access to fresh, reasonably priced crab meat, add 1/2 pound of it to this dish!

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 small onion, peeled and thinly sliced

2 cups coconut milk

1 teaspoon dried Mexican oregano

1/4 teaspoon ground achiote (annatto)

1 medium red bell pepper, cut into 1/4 inch strips

1 1/2 pound fish filets (red snapper, sea bass or tilefish) cut in 2-inch pieces

1 pound medium shrimp, shelled and deveined

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon fresh ground black pepper

1 medium plantain, peeled and chopped

1 medium tomato, diced

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons minced cilantro leaves

Freshly grated coconut

Pour the vegetable oil into a large skillet over medium heat. Add the onion and red pepper and saute until softened, about 1 minute.

Add the coconut milk, oregano and achiote and bring the mixture to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer about 5 minutes, until it starts to thicken. Add the plantain, tomato and seafood and simmer just until the seafood is cooked, about 10 minutes.

Season to taste with salt and freshly ground black pepper. Garnish with minced cilantro and freshly grated coconut and serve.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Mild

Ceviche de Ostras

(Guatemalan Oyster Ceviche)

This dish gets its heat from habanero chiles and a delicious twist from fresh mint. Make it when you have access to plenty of fresh oysters. If you don’t have a habanero, you can substitute jalapeños. This recipe requires advance preparation.

48 oysters, shucked

1/2 cup fresh lime juice

1/2 cup fresh lemon juice

3 tomatoes, peeled, seeded and chopped

1 cup chopped onion

1 habanero chile, stemmed, seeded and minced

3 tablespoons finely chopped fresh mint

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Garnish:

Lettuce leaves

Fresh mint sprigs

Tomato wedges

Place the oysters in a large ceramic bowl and cover them with the lime and lemon juices. Cover the bowl tightly and refrigerate overnight.

Drain the oysters and reserve 1/4 cup of the juice. Add the remaining ingredients to the oysters, along with the reserved juice, and toss the mixture gently.

Line 6 plates with the lettuce leaves, arrange 8 oysters on top of the lettuce and garnish with fresh mint and tomato wedges.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium